Why designing theater sets has shown me museum exhibition design can (and should) be so much more than a white box

By HannaH Crowell

Four years ago, I took my career off the stage and into the gallery. After working as a freelance theatre designer for many years, I joined The Mint Museum staff as the exhibition designer in 2016.

Inspired by art since childhood, theatre revealed itself as a form of creative expression that combined my love for art and storytelling. The daughter of an amazing storyteller, I knew from an early age that I wanted to be a storyteller, too. But I wanted to create spaces where these stories came to life.

Those early formative years have led to a career focused on crafting the immersive art experience, emphasizing audience engagement and finding new ways to tell stories. And while I now work full-time in the museum world, I’ve kept my foot in the arena of theatre design, often designing for Children’s Theatre of Charlotte.

The transition from theatre to museum work has redefined how I use design to interpret space and engage an audience in a story. But, there are three lessons theatre has taught me that I bring to each new project.

Curtain up! The big reveal sets the scene

When the lights go down in the theatre, just before the curtain rises, my heart skips and I tear up. It’s been this way since I was a kid, and when I started working in theatre I didn’t become numb to it—I learned to design for it. The big reveal is not just part of the magic, it’s the first impression you give your audience of the world you’ve created for the story.

Of course, we can’t raise a curtain for every visitor to a museum gallery, but I work to design each Mint exhibition entry in a way that still gives the visitor that big reveal. For most exhibitions, the entry begins with a title wall that provides a brief introduction to the exhibition concept. I want ours to go one step farther: to set the rhythm and atmosphere for the visitor’s experience.

For Under Construction: Collage from The Mint Museum, an exhibition exploring the dynamic medium of collage that opened December 2018 at Mint Museum Uptown, I wanted to give the visitor a tactile experience upon entering. So we created a wall, where visitors could tear off each letter of the exhibition name. By tearing away a layer of the title wall, the visitor would participate in an ever-evolving collage and better understand how a collage is made through the layering, tearing, and subtracting of materials.

The exhibition “Under Construction” included an interactive element that allowed visitors to help create an ever-evolving collage. Photos by Brandon Scott

Sometimes, though, the big reveal of an exhibition entry needs to transport the visitor into an entirely new world. For the Mint Museum’s exhibition Michael Sherrill Retrospective—on view from October 2018 through April 2019 at Mint Museum Uptown—it was important that upon entry, the visitor develop a strong connection to the artist Michael Sherrill, known for his groundbreaking work with clay, glass and metal.

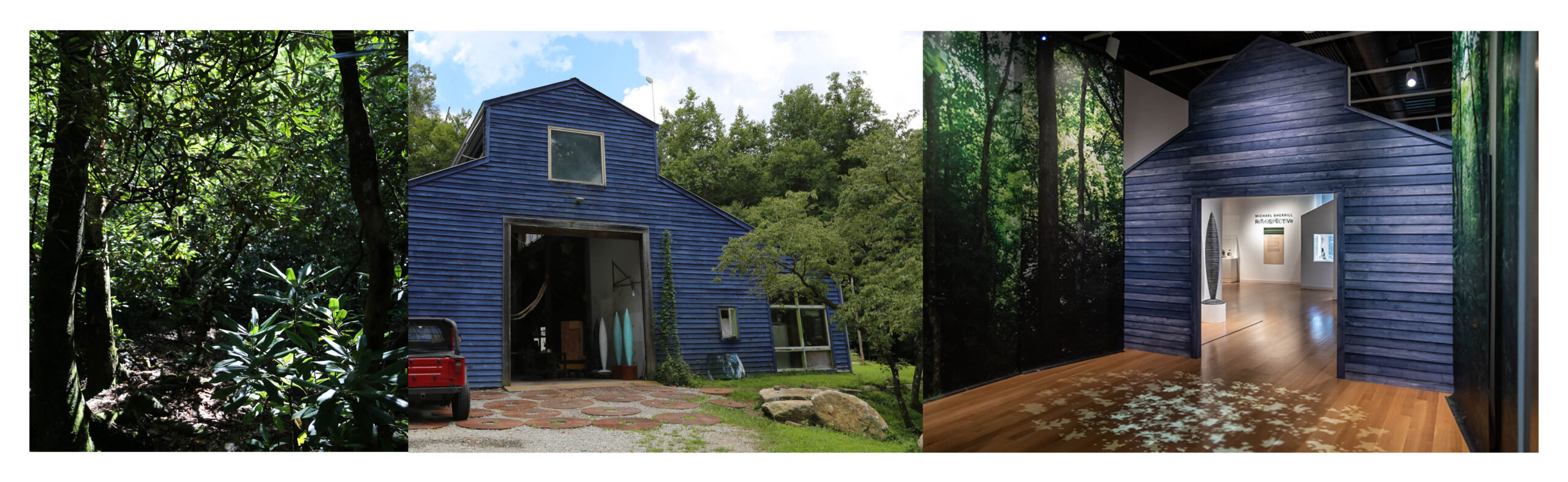

For Michael Sherrill Retrospective, I took a far more atmospheric approach, designing an environmental treatment that immersed the visitor in the lush green forest of western North Carolina, set against the cobalt blue stained wood planking matched to Michael’s Studio. The entry transitions the visitor seamlessly between interior and exterior spaces inspired by Michael’s studio space and surrounding property.

Left to right: A visit to Michael Sherrill’s property. Photos by HannaH Crowell. The exhibition entrance to “Michael Sherrill Retrospective” at Mint Museum Uptown. Photo by Brandon Scott

Listen to what the characters have to say

The first step in any theatre design process is reading the script. Each character is an essential part of the story, and the playwright has given important information that defines the world of the play—and the design—in the character’s dialogue. The first step in an exhibition design process is reviewing a document similar to a script, known as a checklist. More like a character breakdown, the checklist gives specific information about each work of art that will be in the exhibition. Unlike a script, the characters in the checklist don’t have speaking lines. And yet, they still speak if you know how to listen.

While it took an adjustment at first when transitioning from theatre to museum design, I learned to rely on the curator, the artist, lots of research and my own intuition to help interpret what the objects have to say and how this informs the world of the exhibition.

For the Mint’s most recent exhibition Classic Black: The Basalt Sculpture of Wedgwood and His Contemporaries at Mint Museum Randolph, I worked with curator Brian Gallagher and did months of research to help interpret what the more than 100 objects—ranging from small portrait medallions to large busts and vases—all of the objects had their own story, so finding a way to weave those stories together to create a seamless narrative was one of the biggest design challenges I’d faced. The other distinctive aspect of these “characters” was that they were all “costumed in black”—or rather, they are all made of a black basalt ceramic material. So one of the first design decisions influenced by our cast of characters was to set them in a world of color. But how to shape the gallery into a stage that each of these characters could come to life?

Inside the galleries at “Classic Black: The Basalt Sculpture of Wedgwood and His Contemporaries” at Mint Museum Randolph. Photo by Brandon Scott

Originally produced in the 18th century, these objects were thriving in the height of neoclassical design. My research lead me through the designs of Robert Adam, whose aesthetic focused on the movement of the eye from floor to ceiling, creating architectural features that would frame these objects within the elegant rooms. For our exhibition, each of the three gallery rooms was inspired by the grand designs of the neoclassical style. The Sculpture Hall for the character that told the story of the classics, The Library for the characters that were the thinkers and the politicians, and finally, for the beautiful characters fit for the finest entertaining, The Drawing Room.

The audience is your most important collaborator

Theatre is a collaborative art. Actors, the director, designers, and stage technicians—they all bring their expertise and talents to the process, but it isn’t until that first performance with an audience that the team is complete. While working as a theatre designer, I was so intrigued by the prospect of designing for an environment where the audience is no longer confined to a theatre seat and can navigate their way through a multidimensional creative moment.

This led me away from the “black box” of the theatre and into the “white box” of the museum gallery. With each new exhibition design project, I learn and apply new ways of creating immersive and engaging spaces for the visitor to create their own stories.

The most theatrical design I’ve yet to do in the museum, the exhibition Never Abandon Imagination: The Fantastical Art of Tony DiTerlizzi needed a design that invited the characters in DiTerlizzi’s illustrations to break out of the white box and come play in the gallery. Designed into the immersive exhibition there where drawing activities, larger than life character cutouts, and books to read and look at so that visitors to the exhibition could interact with the characters the book they live in, creating their own stories.

Inside the gallery at the “Never Abandon Imagination: The Fantastical Art of Tony DeTerlizzi.”

I still return to the theatre to remind myself of these lessons and learn new ones that might help make me a stronger designer—for the stage or the gallery. Last fall I worked with Children’s Theatre of Charlotte on their world premiere production of The Invisible Boy. Part rock concert and part picture book, the scenic design brought the beloved children’s story by Trudy Ludwig to life, pulling inspirations directly from the pages of this thoughtful book about a boy, Brian, whose vivid imagination becomes a canvas for his creativity.

On set at Children’s Theatre of Charlotte’s “The Invisible Boy” performance. Photos by John Merrick