Lumisonica, the interactive light and sound installation designed by Vesna Petresin for the Grand Staircase at Mint Museum Uptown and scheduled to debut this November, marks the Mint Museum’s first experience with this kind of multimedia, interdisciplinary, intangible art. To recap a previous blog post, Lumisonica is “based on the concept of a smart, playable city. It encompasses disciplines from architecture, lighting design, sound design, choreography and set design, to interactive visual arts.”

Communications with Petresin about her ideas and inspirations have been an intellectual adventure. On one hand, the physical components for Lumisonica are straightforward: LED lights that can display a range of colors mounted in the hand railings and on the large steps near the treads; speakers at various points on and near the staircase; and infrared sensors that detect visitors’ movement. What is remarkable, however, is how Petresin is composing a complex, ever-changing light- and soundscape based on a wide array of predetermined color schemes, musical tones, and other sounds, which shift based on factors such as time of day, light level, and season, as well as when triggered by visitors crossing the sensors. The score for these sound and light effects will be programmed into a Pharos show controller using Pharos Designer 2 software.

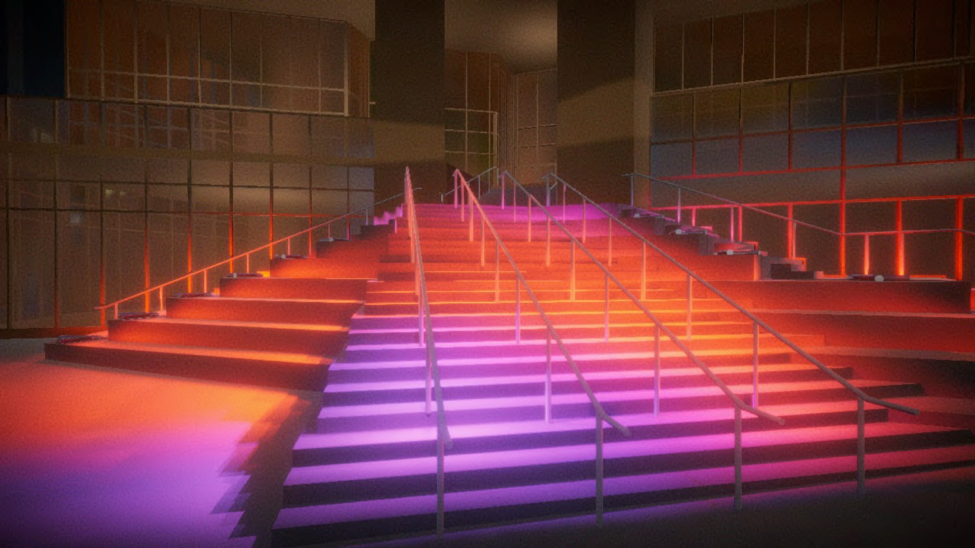

Simulation of staircase lighting at night. Image courtesy of Vesna Petresin

The auditory source material Petresin is drawing upon falls into four categories. Firstly, she is incorporating the sounds of nature, such as water flowing, wind, crackling leaves, and pebbles underfoot. Petresin wants visitors to feel as if they are walking on natural materials that make sounds on impact, so the staircase feels more alive and organic. In a similar vein, bass transducers will amplify the sounds of visitors on the staircase, creating echoes that magnify the perceived size of the staircase and mimic the experience of being in a resonant space such as a cave or on top of a mountain.

The third and fourth categories of sound prompt fascinating forays into the history of musical composition. Petresin uses the Solfeggio Frequencies, originally a series of six tones—a hexachord—ranging from 396 to 852 Hertz (a measurement of frequency in cycles per second). They date from the Middle Ages, when musicians composed using hexachords instead of today’s octaves. The Solfeggio Frequencies are a hexachord used in a hymn to Saint John the Baptist known in Latin as Ut queant laxis. During the eleventh century, a Benedictine monk, Guido of Arezzo (born around 991 or 992), seeking a mnemonic device to teach music to other monks, gave each note a name derived from the first syllable of each musical phrase, which also presented the hexachord from lowest to highest note. These names were Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, and La; “solfeggio” derives from Sol and Fa. From this one hexachord’s named notes came a system that has been widely used to teach music. If you’ve ever seen The Sound of Music, you are already familiar with it. To accommodate octaves, a seventh note, Si, was added later and eventually changed to Ti, and Ut was later changed to Do. Hence, Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do.

Photo by Markus Gjengaar on Unsplash

Petresin chose to use the Solfeggio Frequencies in Lumisonica based on having read a study in which they were played in public spaces and passersby subsequently reported feelings of calm and well-being. While it remains unproven whether the Solfeggio Frequencies have unique beneficial effects, it is well-known that music can alter our emotional and physiological states. Indeed, most people can cite examples of music that they find happy or sad, calming or aggravating.

Petresin’s method of deriving a variable musical score from the sounds of nature, visitors, and Solfeggio Frequencies is equally interesting. She is inspired by the avant-garde twentieth- and twenty-first century composers Philip Glass (American, born in 1937), Steve Reich (American, born in 1936), and György Ligeti (Hungarian-Austrian, 1923–2006). All three composers are known for their atonal approach to music. Eschewing Western classical music’s traditional focus on harmony and melody, these composers instead build textured soundscapes using layers of instruments, voices, and sounds playing repeated motifs. These soundscapes blend instruments associated with Western classical music with those from other traditions such as ocarinas, sitars, didjeridus, pipas, and more, as well as electronic instruments.

Philip Glass is a household name thanks to his more than fifty film scores; his collaborations with pop musicians such as David Bowie, Paul Simon, and David Byrne; and his numerous operas, symphonies, concertos, and scores for dance performances. Glass studied flute in the college-preparatory program of the Peabody School of Music as a teenager in Baltimore. He went on to study mathematics and philosophy at the University of Chicago, graduating in 1956 at age nineteen. He earned an MS in musical composition from the Juilliard School of Music in New York in 1962 and studied composition in Paris under Nadia Boulanger. He also met Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar there, who influenced his atonal compositional style. Glass’ biography on his website notes that “much of his early work was based on the extended reiteration of brief, elegant melodic fragments that wove in and out of an aural tapestry.”

Photo by Radek Grzybowski on Unsplash

Steve Reich similarly draws upon world music traditions as well as modern technology. His studies include a BA with honors in philosophy from Cornell University (1957); the study of composition with Hall Overton (1957–1959); at Juilliard (1958–1961); and an MA in composition from Mills College (1963). He also studied drumming at the University of Ghana in Accra; Balinese gamelan in Seattle and Berkeley; and traditional chanting of Hebrew scriptures in New York and Jerusalem. Reich is noted for discovering “tape-based techniques of looping and phasing using recordings of fragments of speech” (Tom Service, The Guardian). Petresin is especially intrigued by Reich’s Clapping Music, in which two individuals simultaneously clap different rhythms to create a complex percussive composition.

György Ligeti’s experiments with music were a response to his experiences with World War II and its aftermath in his native Hungary. As Jews, his family was imprisoned by the Nazis; his father and brother died in a concentration camp, his mother survived Auschwitz, and György escaped from a slave labor camp as a teenager. After the war, he studied music and became a composer and teacher in Budapest. When the Soviets invaded Hungary in 1956, Ligeti fled to Cologne (then in West Germany), joining a group of innovators in electronic music led by Karlheinz Stockhausen (German, 1928–2007). Ligeti’s music excels equally at conveying cosmic profundity and absurdist humor, often at the same time. He achieved broader recognition when Stanley Kubrick used his music in 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Shining. Petresin is particularly influenced by Ligeti’s Poème Symphonique for 100 Metronomes, which creates rhythm from the staggered ticking of 100 of these devices.

The Solfeggio Frequencies and the influences of Glass, Reich, and Ligeti are all part of the third category of sounds Petresin is drawing upon for Lumisonica. The fourth category comes from yet another area of musical history: arpeggios from Les Miroirs (The Mirrors, 1904–1905), a five-part piano suite by Maurice Ravel (French, 1875–1937), will occasionally play on the staircase to highlight important events at the Mint Museum. Ravel studied music at the Paris Conservatoire from 1889 to 1905 and thereafter mostly led a quiet life composing. Among his other notable works are Daphnis et Chloé (1909–1912), for the Ballet Russes, and Boléro (1928), for Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein.

Photo by Kyle Arcilla on Unsplash

The sound clips of Les Miroirs in Lumisonica were performed by the preeminent classical pianist and North Carolina native, Vivianne Cheng (born in 1990). Cheng gave her debut recital at age ten and entered Juilliard at age fifteen. She has also studied at the Universität Mozarteum Salzburg, and this spring was a student of Petresin’s at the University of Amsterdam, where she researched Ligeti’s work. Les Miroirs was already in Cheng’s repertoire, and Petresin found that it had “exactly the sort of character, clarity and brilliance that the environment of the stairs required.” Cheng plays the piece’s first movement, “Les Noctuelles,” starting at 7:15 in this clip. She will return to North Carolina to give two recitals in Chapel Hill this December.

By synthesizing the sounds of nature and visitors, the Solfeggio Frequencies, passages from Ravel, and inspirations from Glass, Reich, and Ligeti, Vesna Petresin is creating what promises to be an endlessly changing, immersive, and unforgettable visual and musical experience for Mint Museum visitors.