The medium is a metaphor

By Page Leggett

Kenny Nguyen is both creator and destroyer. The native of Vietnam, who now lives in Concord, explains, “If you want to do something new, you have to destroy something and rebuild it.”

His elegant, ethereal art made from paint-soaked silk looks serene. There’s no trace of the demolition involved in making it. The reason he tears down only to build back up goes deeper than aesthetics. The deconstruction (and reconstruction) mimics his own seismic cultural shift.

Nguyen and his family left Vietnam for Charlotte when he was 19. His use of silk is an homage to his homeland; Vietnam produces some of the world’s finest. Once he arrived in the United States, he felt as though he had to start everything all over again. “It was like I was being deconstructed,” he says. “I had to reconstruct my identity. If you move somewhere and don’t know anybody and don’t speak the language, it’s very isolating. I didn’t know who I was anymore.”

Portrait of the artist as a young child

Nguyen grew up in a small village in the Mekong Delta. Its size and remoteness forced him to make his own fun.

“We were very isolated,” he says. “There was no road connecting us to anything, so we traveled by boat. I didn’t have access to a playground or toys. If I wanted to play with something, I had to make it myself. My mom and dad introduced me to watercolors when I was 4 or 5, and I spent much of my childhood painting and drawing. It never left me.”

At 17, he moved to Ho Chi Minh City to study fashion design. But that wasn’t the biggest culture shock he’d experience. That happened three years later in 2010 when the family moved to Charlotte. Nguyen switched course and studied fine art, earning a bachelor’s degree in painting from UNC Charlotte in 2016. After graduation, he pursued art while also working part-time at a nail salon. The pandemic, while devastating for many, brought Nguyen good fortune. Thanks to social media, that is when he made the leap to full-time artist. Social media has no geographic boundaries, so when he shared his work online, collectors all over the world took notice. Prestigious galleries found him and he sold more in 2020 than ever before.

Nguyen is now among Sundaram Tagore Gallery’s artists, all of whom, according to the gallery’s website, “produce museum-caliber work.” The contemporary gallery, with locations in Singapore and London, specializes in “work that is aesthetically and intellectually rigorous, infused with humanism and art historically significant.” He’s exhibited in France, Iceland, and South Korea and recently returned from Büdelsdorf, Germany, where he was part of an international group show.

A melting pot of materials

There’s a lot of physicality to Nguyen’s art-making process. He creates his large-scale work on the floor of his studio. He cuts the silk and soaks the strips — often, hundreds of them — in acrylic paint. While those strips are still damp, they’re affixed to a canvas. The wet, thick paint acts as an adhesive.

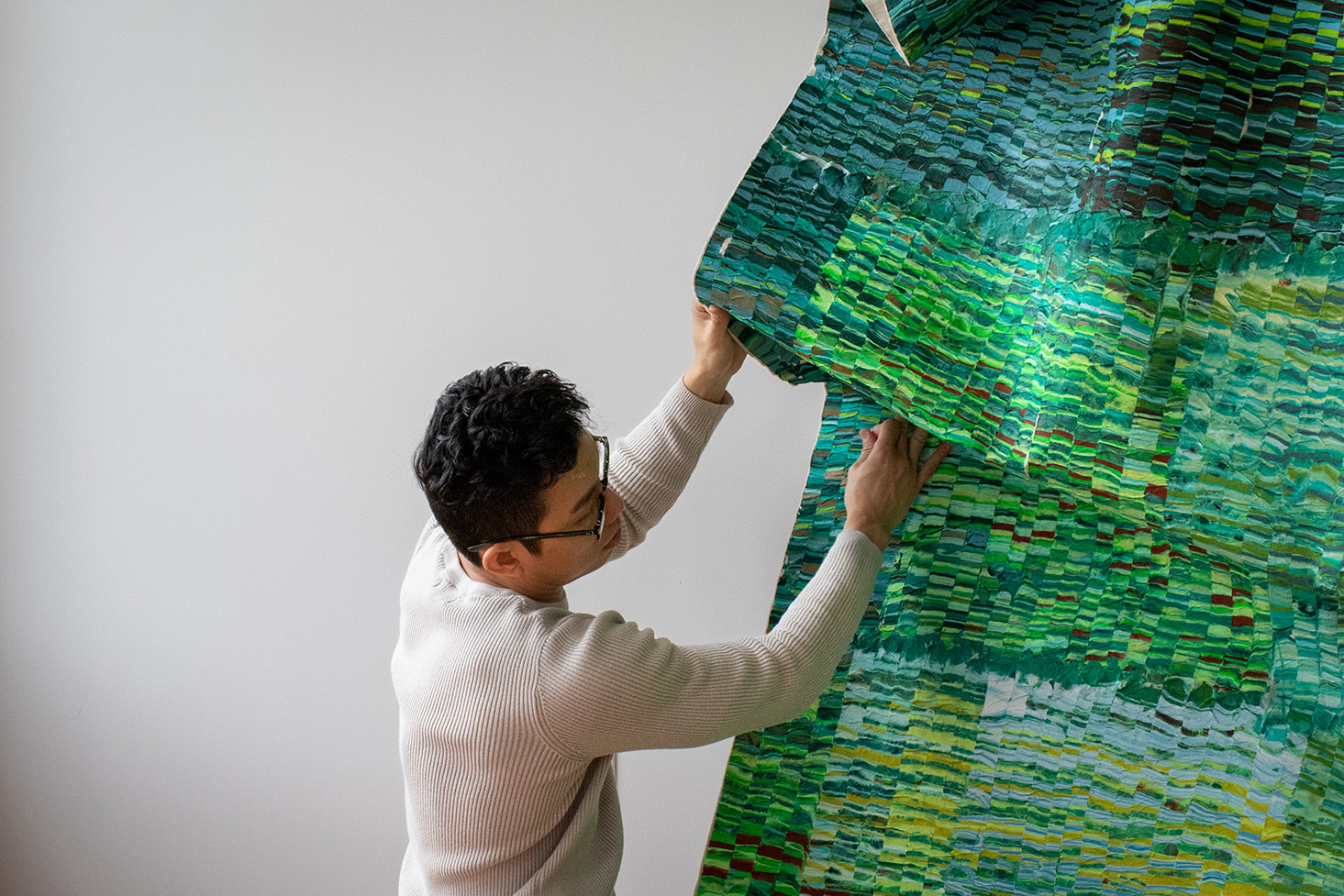

The finished work has three layers: silk, paint, and canvas. Although they are tightly integrated, it is hard to tell where one piece ends and another begins. The fabric maintains its character while also becoming something new once he assembles the strips with pushpins, a holdover from his fashion design days. Once he finishes a work on the floor, he hangs it on a wall in his studio for more tinkering. The painted silk strips can be placed in different configurations on canvas. Pushpins allow him to gently sculpt the pieces into undulating folds. “One piece can take many different forms, just like our identities, which are always changing.”

Performance art

Nguyen’s collectors often tell him they have never seen anything like his art. His installation process is as labor-intensive as his creative process. It is not uncommon for a collector to film him working. One New York collector, born and raised in Vietnam, tells him it reminds her of home. “It’s always meaningful when collectors connect with my work,” he says. “These aren’t typical ready-to-hang paintings,” he explains. “My work is much more complicated. It needs to be installed. When I do an installation, it’s sort of like a performance. My collectors witness the art come alive as I rebuild it on their wall. I think it adds to the joy of collecting.”

When Nguyen invented the process he uses to make his “deconstructed paintings,” he wasn’t sure others would get it, but Sozo Gallery founder and owner Hannah Blanton did. Shortly after Nguyen’s graduation, Blanton’s now-closed uptown gallery began representing him and did so until Blanton closed Sozo and opened her art consultancy business seven years later. Today, she serves as studio director for Nguyen. Nguyen credits Blanton with promoting his work and helping explain its complexities to potential patrons.

Indeed, his work is mysterious. “People always want to take a closer look, because it’s almost an illusion tricking you,” he says.

The artist who once felt like a stranger here now considers Charlotte his second home. (Vietnam is still first.) “I’m grateful for the large art community here that encouraged and supported me,” he says. “When I talk to young people who want to start an art career here, I’m happy to tell them they don’t have to move to New York to make it.”

Page Leggett is a Charlotte-based freelance writer. Her stories have appeared in The Charlotte Observer, The Biscuit, Charlotte magazine and many other regional publications.