“I think art has the ability [to], if not cure or heal, at least enlighten, slap you in the head, wake you up,” —artist Joyce J. Scott

Franco Moschino (Italian, 1950–94), Moschino LLC (1983–). “In Love We Trust Jacket,” 1989, wool and mixed media. Museum Purchase: Funds provided by Deidre and Clay Grubb. 2015.20.4

Art has been created as a response to social unrest and inequality throughout history. It also can serve as a catalyst for hard conversations about racism, the need for cultural understanding and the challenges before us regarding unity and justice. Following are eight curator selections of artwork in the Mint collection that were created in response to violence, racism and cultural disparities that challenge our society.

Wedgwood (Staffordshire, England), William Hackwood, modeler (British, circa 1757–1839). “Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade Medallion,” designed in 1787, jasperware, silver. Delhom Collection. 1965.48.85

This medallion depicts an enslaved black African man, down on one knee with his arms and ankles in chains. Around the medallion’s edge is the inscription, “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?” Josiah Wedgwood first produced this in 1787, the same year that the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in London. Wedgwood joined the society and paid for all the other members to receive a medallion at his expense. See more from Josiah Wedgwood in the gallery tours of Classic Black: Black Basalt Sculpture of Josiah Wedgwood and His Contemporaries. —Brian Gallagher, Curator of Decorative Arts

Augusta Savage (American, 1892-1962). “Gamin,” circa 1930, painted plaster. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Mint Museum Auxiliary. 2008.58

Throughout her career, Augusta Savage fought against racism and sexism as she strove to learn her craft. She constantly strove to uplift children and aspiring artists, first at her Savage School of Arts and Crafts, and later as the founding director of the Harlem Community Arts Center. While some of her portraits celebrated leaders in the African American Community, such as W.E.B. Dubois and Marcus Garvey, other, like Gamin—one of her most popular works—found dignity and hope in the children struggling for survival on the streets of her Harlem neighborhood. —Jonathan Stuhlman, Ph.D., Senior Curator of American Art

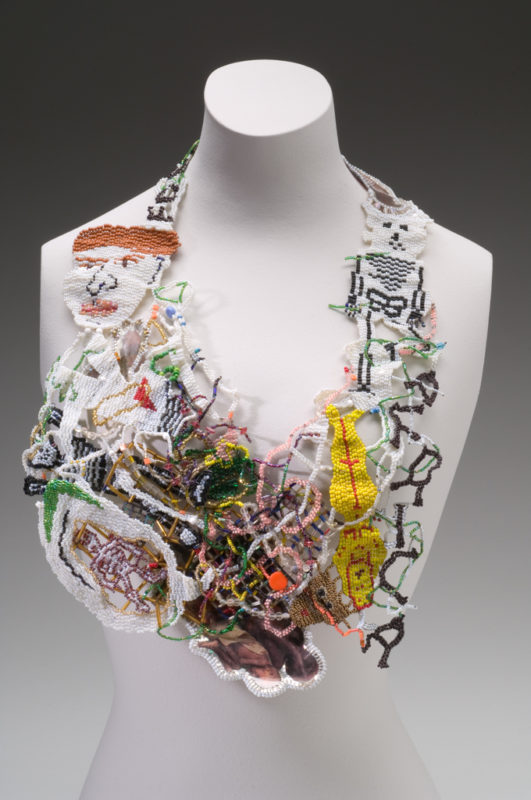

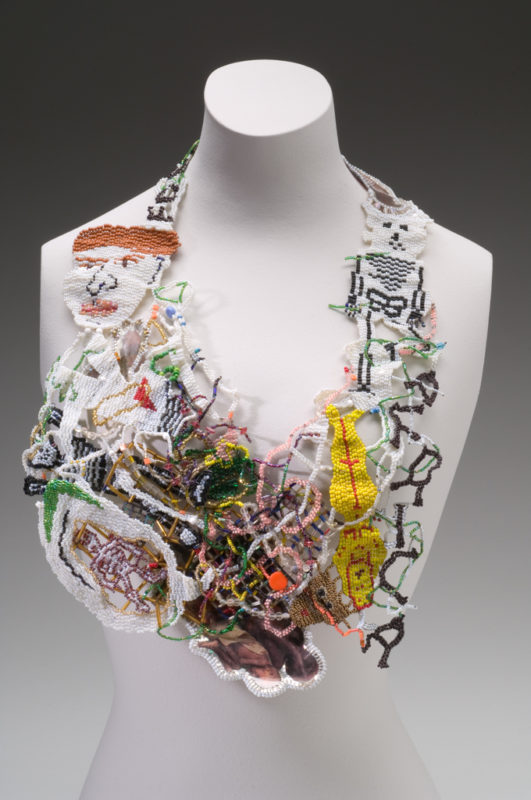

Joyce J. Scott (American, 1948–). “Hunger,” 1991, hand-beaded glass, thread, photographs, plastic. Gift of the Friends of the Mint. 1992.23. © Joyce J. Scott, 1991

Born, raised, and based in Baltimore, Maryland, African American artist Joyce J. Scott confronts racism, sexism, classism, and other issues head-on in art made in a range of media. Her 1991 necklace Hunger addresses famine in Africa—a persistent problem in the 1980s and early 1990s—and white complicity in it. Hand-beaded skeletons and photographs of malnourished children are juxtaposed with a large white face that seems to look away, ignoring their suffering. Hunger is on view at Mint Museum Uptown. In the words of Joyce J. Scott, “I think art has the ability [to], if not cure or heal, at least enlighten, slap you in the head, wake you up.” —Rebecca Elliot, Assistant Curator of Craft, Design and Fashion

Leo Twiggs. (American, 1934–). “Conversation, 2018,” batik on linen. Museum purchase with funds from the Charlotte Debutante Club. 2018.44

In 2016 The Mint Museum exhibited Dr. Leo Twiggs’ powerful cycle of nine paintings created as a tribute to those who lost their lives in the shooting at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina. In this series, Dr. Twiggs sought to inspire reflection, redemption, and ultimately, healing. The museum commissioned this painting following its presentation of that exhibition. Conversation was inspired by comments that visitors left for Dr. Twiggs during the exhibition. As the artist has noted, “Since the Mother Emanuel paintings were used at every exhibit venue as a catalyst to create conversations about race and culture, I was inspired to do a painting I call Conversation.” While art can sometimes be an escape from current events, it can also inspire us to have difficult but necessary discussions with those who think differently than we do. —Jonathan Stuhlman, Ph.D., Senior Curator of American Art

Nick Cave (American, 1959–). “Soundsuit,” 2007, fabricated, beaded, and sequined body suit, metal armature, metal Victorian flowers. Museum Purchase: Founders’ Circle Annual Cause. 2009.19.1A-OOOOO. © Nick Cave

Nick Cave’s first Soundsuit was created in 1992 as a direct response to the shocking event of the brutal beating of Rodney King by 4 Los Angeles police officers and the riots there that followed. As a black man, Cave felt the injustice of racial profiling, recognizing that society dismissed and discarded African-Americans. He began collecting twigs, discarded objects he found at the railroad tracks, textiles and objects from flea markets and thrift shops, undervalued and unwanted things. Such materials became costumes complete with headdresses and masks to conceal the identity of the wearer. A “secondary skin” that disguises race, gender, and class,” the Mint’s Soundsuit is made up of a rainbow of multicultural embroideries and knitting, and a chandelier from a junk shop in Indiana. —Annie Carlano, Senior Curator of Craft, Design & Fashion

Franco Moschino (Italian, 1950–94), Moschino LLC (1983–). “In Love We Trust Jacket,” 1989, wool and mixed media. Museum Purchase: Funds provided by Deidre and Clay Grubb. 2015.20.4

Best known for his fine tailoring and irreverent fashion designs that often included provocative quotes, Franco Moschino created his eponymous couture and ready wear company at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Europe, where gay men afflicted with the virus were often ostracized and ridiculed by society. Working within the more conservative fashion industry in Milan, Moschino was dubbed the “enfant terrible” for his extreme creativity and use of clothing as communication for his personal politics and humanitarian causes. In Love We Trust, is a jacket that illustrates the designer’s compassion, with an image of a cow as a symbol of his support of animal rights, and the words and red heart needing no explanation. The year before his death he founded a hospice for children with AIDS. —Annie Carlano, Senior Curator of Craft, Design & Fashion

Barbara Pennington (American, 1932–2013). “Selma,” 1965, oil on canvas. Museum purchase with funds provided by Peggy and Bob Culbertson, the Romare Bearden Society, Sally and Russell Robinson, Mary Lou and Jim Babb, and a gift of the Moreland Family. 2014.79

This remarkable painting was created in response to the heart-wrenching events that unfolded in Selma, Alabama, in the spring of 1965. Barbara Pennington, an Alabama native, was training in New York at the time of the Selma marches and attacks. The events unfolding in her home state inspired her to create this monumental canvas. Likely drawing upon images that appeared in the mass media, Pennington wove together various parts of the narrative into a gut-wrenching scene that remains a powerful, moving representation of these tragic events—and the ways in which they can unify people from all walks of life to come together to demand change—more than 50 years later. —Jonathan Stuhlman, Ph.D., Senior Curator of American Art

Diego Romero (Cochiti, 1964–). Bowl, late 20th century, earthenware with slip paint. Gift of Gretchen and Nelson Grice. 2017.43.34

Cochiti artist Diego Romero, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, combines the graphic influences of ancient Mimbres pottery and 20th-century American comic books on his illustrated pots that comment on life as a contemporary Native American, including challenging social issues such as alcoholism and poverty. Seen here are his recurring characters the Chongo Brothers, inspired by the mythical Mimbres hero twins, but also by the artist’s childhood with his brother Mateo; chongo, a traditional bun hairstyle, became a nickname for the two boys. This bowl is on view at Mint Museum Randolph. —Rebecca Elliot, Assistant Curator of Craft, Design and Fashion