Genaro Rivera

1861–1941, Morovis

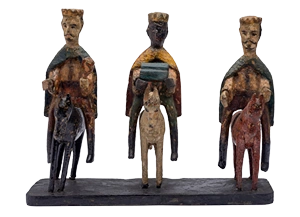

The Three Kings Standing circa 1935

Wood, paintGenaro Rivera uses paint to emphasize the woven designs on the Kings’ tunics in contrast to carved lines to accentuate the landscape and architecture.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 158

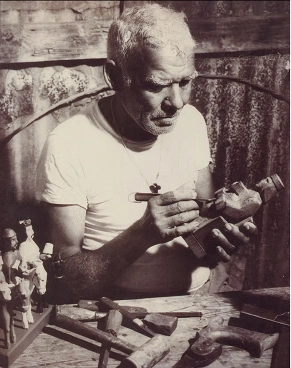

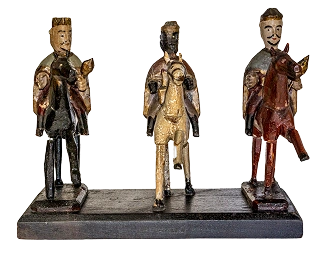

Carmelo Soto Toledo

1906–2004, Lares

The Three Kings Standing 1997

Wood, paintCarmelo Soto epitomizes the traditional santero as being primarily a farmer, a multi-talented handyman, a faithful husband and father, and a man of faith. He also was an outstanding maker and player of the Puerto Rican cuatro, a small guitar-like instrument. Soto Toledo often participated in Epiphany celebrations playing the cuatro and singing décimas, poetic songs honoring the Three Kings. His repetition of forms visually resembles the regular beats of a musical composition and a recited poem.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B309

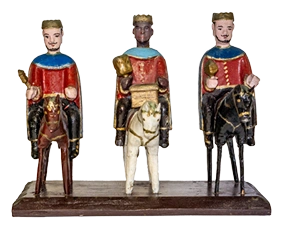

Genaro Rivera

1861–1941, Morovis

The Three Kings on Horseback circa 1890

Wood, paintSome santos compositions are low-relief carvings on a flat rectangle of wood, intended as a wall hanging. Note Rivera’s use of thin carved lines to emphasize the tall grass and hilly terrain—a landscape much like that of his hometown of Morovis.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 309

Master Santero of Aguada (Name Unidentified)

Late 18th–19th century, Aguada

The Three Kings Late 18th–early 19th century

Wood, paintThis masterful carver’s works are distinguished by his excellent carving and painting skills. The variations in each King’s facial features suggest portraiture, a rare quality in the santos tradition. Note the horses’ energetic poses and the colorful design motifs of the Kings’ attire.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B5

Luis Román Ramos

born 1975, Quebradillas

The Three Kings Triptych 2007

WoodLuis Román Ramos’ santos are carved from technically challenging hardwoods, yet he captures the calm spirituality and individualism of the sacred figures. For example, note the skilled carving of the Kings’ beards replicating their different hair textures. In place of pigment, Román Ramos retains the aesthetic appeal of natural wood finishes. Here he selected woods with different colors and characteristics to distinguish each of the Three Kings’ garments.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B133

Rafael “Fito” Hernández

1932–2004, Camuy

The Three Kings on Horseback 1997

Wood, paintKnown as an accomplished musician, singer, and baseball player, Fito Hernández was also a skilled carver. Living in the same town as the widely recognized master carver Florencio Cabán, Fito’s style features similarly posed geometric figures and precision painting that pay homage to his fellow Camuy santero.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 284

Florencio Cabán Hernández

1876–1951, Camuy

The Three Kings on Horseback circa 1940

Wood, paintPretty faces and simplicity of form characterize Florencio Cabán’s carvings. He was dedicated to the Three Kings because he believed they answered his prayer to secure a house for his family. Florencio takes great care in the decoration of the Kings and often pictures them with blue eyes like his. He is the first santero recognized outside of Puerto Rico as a masterful carver.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 95

Unidentified Puerto Rican Carver

19th century, Puerto Rico

The Three Kings (on springs) 19th century

Wood, paint, metal springs, horsehairThe use of small springs to support the Three Kings on horseback is an unusual trait of 19th-century carvings of the Three Kings. The springs may have been used to convey galloping horses. This curious practice disappears during the 20th century.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B112

Florencio Cabán Hernández

1876–1951, Camuy

The Virgin of the Three Kings circa 1930

Wood, paintThe Virgin’s charming face is the focal point of this sculpture, which is also a key characteristic of Florencio Cabán’s facial renderings. He and his brother Manuel were the first to depict only the Three Kings’ heads placed along the hem of the Virgin’s tunic in place of its usual decorative border.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 308

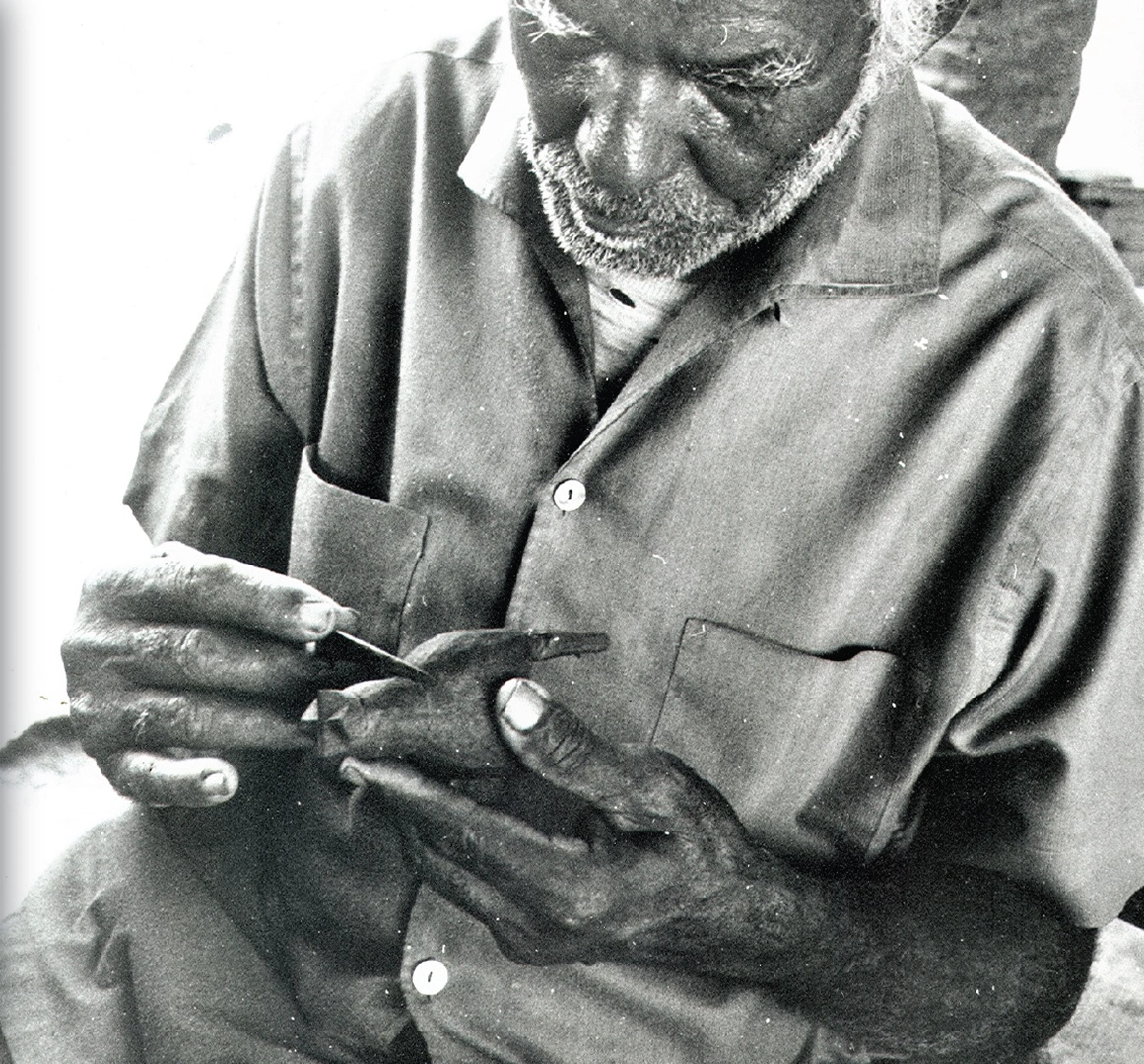

Ceferino Calderón Abaladejo

1911–2004, Morovis

The Virgin of the Three Kings 1998

Wood, paintCeferino Calderón’s unmistakable style is testament to his natural talent as an interpreter in wood and paint. He is considered a traditional santero in making his living as a farmer and carpenter and expressing his faith through carving sacred images.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B320

Carlos Vázquez Sánchez

1904–2003, Ciales

The Virgin of the Three Kings 1996

Wood, paint, metalThis carver is known for his early works in unpainted wood on which he carved rounded forms and deep, curved lines to suggest the human body, the natural folding of garments, and decorative embroidery. As his advancing years made such intricate carving impossible, Carlos Vázquez turned to paint to accentuate his now-shallow incisions. Nonetheless, his later painted pieces, such as this example, preserve his inimitable style. One King holds a string of small metal offerings, called milagros, which are cut metal (often silver) icons bestowed on the saint by a worshipper in thanks for their answering a prayer for divine mediation of an earthly problem.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B356

Juan Cartagena Martínez

circa 1887–1956, Orocovis

The Virgin of Montserrat circa 1950

Wood, paintThe carver follows the traditional format for Our Lady of Montserrat although he accentuates the mountain’s saw-tooth outcrops at the top of the carving, painting them black with white lines to denote their ruggedness.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 99

Unidentified Puerto Rican Carver

19th century, Puerto Rico

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1890

Plaster, wood, paintOur Lady of Montserrat sits on a high-back throne set against the Catalonian mountains where her shrine is located. The somewhat muddy colors of this piece are the result of many reverential repainting for special observances, a common occurrence especially for older santos de palo.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B82

Héctor Moya Montero

1930–2019, San Germán

Our Lady of Montserrat 2000

Wood, paint, recycled clock frameThe carver follows the traditional format for Our Lady of Montserrat—a flat frontal position with Jesus on her lap and both holding a golden globe. The requisite mountain is depicted as abstract vertical spikes with golden highlights. This modernist rendering closely parallels the actual mountain in Spain with its pointed outcrops like the teeth of a saw (Mont Serrat or “Serrated Mountain”). Héctor Moya’s first santo was Our Lady of Montserrat, carved in thanks for his recovery from an operation. She sits in a niche made from the recycled frame of a grandfather clock.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 312

Pedro Arce Sotomayor

circa 1857–1951, Arecibo

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1920

Wood, paintAlong with the Three Kings, Our Lady of Montserrat receives the most “promises” from Puerto Rico’s faithful who petition the Virgin to heal ailments of persons or farm animals, a damaged body part, or any other affliction. When prayers are answered, the petitioner commissions metal icons known as milagros, which depict the healed entity. The variety of milagros hanging on this Virgin reveals the many “promises” from devoted petitioners over time.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 145

Pedro Rosa (Pedro Cuperes Vásquez)

circa 1870–1957, San Sebastián and Lares

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1920

Wood, paintPedro Rosa combines a realistic face with an abstract figure, its frontal position emphasized by the curvature of the Virgin’s cloak. His faces are considered among the prettiest in the santos corpus, and he often sculpts the eyelids and outlines them with a minute tiny incision.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 112

Eduardo Vega

born 1944, Cabo Rojo, Camuy

Our Lady of Montserrat 2002

Wood, paintOur Lady of Montserrat is one of the Black Virgins of Europe. Her black skin likely is not an indication of genetic origin but instead results from centuries of burning candles in her sanctuary in Catalonia. As a Puerto Rican statement, Eduardo Vega reinterprets the Virgin with African and European features as an accurate reflection of Puerto Rico’s multi-ethnic populace. Her blue cloak decorated with gold stars may pay homage to the Virgin of Guadalupe, the patron Virgin of the Americas.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 18

Ceferino Calderón Abaladejo

1911–2004, Morovis

The Miracle of Hormigueros 1998

Wood, paintAs a master carpenter, Calderón respects the shape and nature of the wood from which he carves santos de palo. This piece evokes the wood block’s geometric form yet breaks its rigidity by adding the separately carved bull and figure of don Gerardo. Calderón carves and paints a zigzag motif across her mantle, suggesting both its decorative edging and the serrated mountains surrounding her shrine near Barcelona, Spain.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B91

Manuel Cabán Hernández

1884–1962, Camuy

The Miracle of Hormigueros circa 1920

Wood, paintLike his brother Florencio, Manuel portrays Our Lady of Montserrat with blue eyes, here in the same turquoise blue as her cloak. Manuel excels in painting details of clothing and the wooden throne’s gilded motifs. Here he даже depicts landmasses on the globe в левой руке Девы Марии.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B380

Florencio Cabán Hernández

1876–1951, Camuy

The Miracle of Hormigueros circa 1930

Wood, paintFlorencio Cabán was among the first carvers to portray the farmer Gerardo González in clothes typical of Puerto Rico’s countryfolk–called jíbaros. These include a broad-brimmed hat usually made of straw, a white or light-colored long-sleeved shirt, and simple pants. The Virgin’s cloak extending into the backboard invokes both the Montserrat mountain in Spain and the tall hill in Hormigueros where González built her shrine. The seven crosses may refer to the seven sorrows of the Virgin Mary.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 320

Unidentified Puerto Rican Carver

19th century, Puerto Rico

The Miracle of Hormigueros circa 1850

Arecibo areaWood, paint, glass, fabric, clay, human hair, metal

This niche-style santos de palo illustrates the key icons of the Miracle of Hormigueros. Our Lady of Montserrat and the Christ Child raise their hands in benediction of the kneeling don Gerardo González facing the humbled bull. The milagros (metal icons) draped around the Virgin were left by worshippers giving thanks for Our Lady’s divine answers to their prayers.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B379

Unidentified Puerto Rican Carver

19th century, Puerto Rico

A Virgin (To Be Dressed) circa 1890

Wood, paint, glassSpanish Baroque sacred sculptures often had a lifelike head and arms attached to a simplified figural framework. The figure would be dressed in opulent attire and adornments specific to the portrayed saint. (See similar sculptures in the Mint’s Spanish Colonial galleries on the 2nd floor.) This example’s fine features suggest she is one of the manifestations of the Virgin Mary. This cannot be confirmed, however, because her vestments and accoutrements are lost. Her eyes are made of imported glass, a key trait of Spanish Baroque sacred sculptures.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B257

Unidentified Puerto Rican Carver

19th century, Puerto Rico

A Christ Child (To Be Dressed) circa 1890

Wood, paint, glassThis figure was carved in five pieces and assembled by joining the arms and legs to the torso. The figure would be dressed in magnificent attire fitting for the divine Christ Child like that on the modern example by Gloria López Estrella (#227, this case). The movable arms allowed the figure to be posed according to the religious ceremony.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 11

Gloria López Estrella

born 1961, Camuy

The Christ Child (Dressed) 2003

Wood, paint, cloth, laceThis contemporary carving of the Christ Child follows the Baroque Spanish template for sacred figures including the jointed arms. López dressed the figure in a conventional lace-trimmed, sleeved tunic. In discussing her work, López says she surrenders her body and soul to the piece as it takes form.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 227

Maestro de la Cordillera (Master of the Mountains)

19th century, central Puerto Rico

The Three Kings (To Be Dressed) 19th century

Wood, paint, metalMany of the 18th and 19th-century carvers remain unnamed and their works indistinguishable from those of other carvers. However, some makers developed specific characteristics that allow us to identify their sculptures. This technically excellent rendering of the Three Kings is by the so-called Maestro de la Cordillera, one of Puerto Rico’s early sculptors renowned for his expert realism. Here he carved the Kings’ bodies unclothed because they were later dressed in opulent garments.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B31

Felipe de la Espada

circa 1754–1818, San Germán

Ecce Homo circa 1780

Wood, paint, glassA hallmark of Felipe Espada’s works is realistic figures and gestures. Note the details of Christ’s hands, their enticing gesture, and the slight tilt of the head. Ecce Homo is the name of images depicting the scourged Christ presented by Pontius Pilate to the hostile crowd prior to his crucifixion.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 280

Felipe de la Espada

circa 1754–1818, San Germán

The Christ Child circa 1790

Wood, paint, glass, metalFelipe Espada’s mastery of naturalism is fully developed in this Christ Child sculpture. Typical of his sculptures are the slightly larger size of the hands in proportion to the body and the wavy lock of hair falling across the forehead.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B388

Felipe de la Espada

circa 1754–1818, San Germán

Saint Anthony circa 1790

Wood, paintFelipe Espada’s smaller figures show his distinct style that came to characterize the entire santos de palo tradition and survives today in contemporary santeros’ works. Primary features are frontal, rigid figures and modified body proportions intended to draw the viewers’ attention to specific attributes of the depicted saint.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 146

Tiburcio de la Espada

1798–1852, San Germán

The Three Kings circa 1820

Wood, paintTiburcio Espada is one Don Felipe’s two sons who made santos. He continues the distinctive Espada traits of carving relatively small faces and deep-set eyes with arching eyebrows. Also typical are the well-defined folds of the clothing, present especially in the tunics as they lay over the Kings’ bent legs and horses’ backs.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 321

Tiburcio de la Espada

1798–1852, San Germán

Our Lady of Mount Carmel circa 1820

Wood, paint, metalTiburcio Espada excelled in the Espada style’s graceful pleating exemplified here in the Virgin’s garments. Other characteristics are the feet sticking out from underneath her robe, the wide-set eyes, and the broad neck. Our Lady of Mount Carmel is venerated in many of the churches and chapels of the Canary Islands, and it is likely immigrants from the islands brought her veneration to Puerto Rico. She is the divine protector of sailors, fishermen, and those who live by the sea and is invoked for safe sea voyages and protection from fierce storms. Thus, her protection was as important in Puerto Rico as it was in the Canary Islands and many seaside communities throughout Spain.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B377

Francisco Rivera (“Pancho el Santero”)

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Saint Theresa of Jesus 19th century

Wood, paintThis figure is more rigid than most of Francisco’s carvings. Yet he spared no effort in depicting the folds of her heavy robe as it falls to the floor. Combined with the graceful curve of her veil, Francisco retains a strong sense of action as the saint directly engages the viewer.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 168

Francisco Rivera (“Pancho el Santero”)

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Saint Anthony 19th century

Wood, paintA fervent sense of movement pervades this otherwise rigid piece. Saint Anthony tilts his head forward and raises his eyebrows as if he has directed a question to the viewer. The Christ child looks up to the saint and gently touches his face. The sense of movement is enhanced by the saint’s bent left leg and robe curving inwards as he leans forward.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 264

Francisco Rivera (“Pancho el Santero”)

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Our Lady of Mercy 19th century

Wood, paint, metalFrancisco Rivera is renowned for his expert carving, which imbues his figures with a keen sense of motion while retaining the formality of Spanish Baroque religious sculpture. Here the Virgin bows forward on a slightly bent knee and extends her right hand to the viewer.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 272

Francisco Rivera (“Pancho el Santero”)

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Saint Barbara 19th century

Wood, paintThe round face and delicate facial features centered in the head are principal characteristics of the Spanish Baroque style incorporated into the Rivera style. Note, too, Francisco’s especially graceful drape of the saint’s mantle. Images of Saint Barbara typically include the tower in which she was confined by her pagan father. And she holds the palm branch typical of martyrs in her right hand. Before her death, she had three windows installed to symbolize the Holy Trinity. Saint Barbara is invoked for safety from lightning and thunder and is the patron saint of firefighters.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 323

Genaro Rivera

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

The Three Kings circa 1890

Wood, paintMany of Genaro Rivera’s figures look like children because of their large heads and small bodies. This child-like impression is accentuated by the small size of the horses relative to the Kings’ bodies.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 306

Genaro Rivera

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Our Lady of Mount Carmel circa 1890

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, 140

Genaro Rivera

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Saint Joseph circa 1890

Wood, paintTypical of Genaro Rivera’s style is figures’ robes cinched at the waist and hanging to the ground with feet peeping from below the hem. He also illustrates simple footwear, a somewhat rare trait. Here Saint Joseph’s mouth is slightly open as if caught in mid-sentence. The thin upper lip and slight bulge of the lower lip distinguish Genaro’s figures.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 126

Genaro Rivera

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Our Lady of Mount Carmel circa 1890

Wood, paint, metalGenaro Rivera is the son of the Rivera family’s founder Francisco Rivera. Genaro’s patron saint was Our Lady of Mount Carmel, and he frequently carved her image as an act of faith and reverence. Both examples display his characteristic delicate brush strokes made with special brushes he fashioned from hen feathers. Genaro also mixed his own paints from plant indigo, annatto (achiote) seeds, and charcoal in a lard base.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 142

Genaro Rivera

circa 1840–1910, Orocovis

Saint Raphael Archangel circa 1890

Wood, paintGenaro Rivera’s carvings are usually made from a single block of wood. Occasionally, however, he carves separate elements which are attached to the figure as seen here in Saint Raphael’s wings. The ornate details of the saint’s short robe epitomize Genaro’s artistic style, the delicate designs made possible by his special hen-feather brushes. Compare Genaro’s painting details to those of his son Rafael and grandson Roberto.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 152

Roberto Rivera Rivera

1945–2005, Corozal

Saint Raphael Archangel with Tobias 1997

Wood, paintSaint Raphael’s main emblem is the fish he carries. Sometimes he will be dressed in pilgrim’s clothing and carry a walking staff (as seen here) with a water gourd attached. The tiny figure in front of Saint Raphael is Tobias who was guided by the saint to cure his father’s blindness.

Roberto follows the Rivera figural style with a large head and small body. He continues his grandfather’s preference for opaque pigments but accentuates the painted clothing with carved lines and shapely contours.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B203

Rafael Rivera Negrón

1887–1980, Corozal

Saint Michael Archangel circa 1970

Wood, paintGenaro’s son Rafael Rivera Negrón and grandson Roberto Rivera Rivera continued the family’s distinctive block-like figures with small bodies and large heads. Rafael uses translucent paints to color his Saint Michael Archangel in contrast to his father’s opaque pigments. Rafael’s carving technique shifts dramatically from his forefathers’ careful knife work, instead forcefully attacking the wood to make it release the saintly figure. Note the deep cuts of the eye sockets and mouth as well as the gouged patterning on the collar and tunic’s pleats.

Saint Michael grasps a short sword in his raised right arm as he stands ready to slay the dragon below. The dragon/devil is indistinctly carved, leaving visible each stroke of the knife that methodically gave birth to the devilish figure hidden in the block of wood.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B288

Tomás Rivera Díaz (“Cabo Tomás”)

circa 1831–1911, Corozal

Saint Rita circa 1870

Wood, paint, metalUnlike his nephew Genaro Rivera, Cabo Tomás follows more naturalistic head to body proportions. He shows Saint Rita with the characteristic bleeding wound on her forehead which is understood to be a stigmata attesting to her religious devotion. It was caused by a thorn from Christ’s crown that lodged in her forehead and made a wound that never healed. She was canonized in 1900 with the title of “Patroness of Impossible Causes.” She also is the patron of abused wives and heartbroken women. The many milagros draped in her hand likely bear witness to numerous prayers from distraught women.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 110

Tomás Rivera Díaz (“Cabo Tomás”)

circa 1831–1911, Corozal

Guardian Angel circa 1870

Wood, paint, metalCabo Tomás was a cousin of Francisco Rivera and trained as a cabinet maker, silversmith, and carpenter. First-rate woodworking skills are evident in Cabo Tomás’s santos de palo which are prized particularly for their very fine sanding—the hallmark of an accomplished cabinet maker. Cabo Tomás’s works have sweet faces with impish grins and a thin upper lip above a fuller lower lip. His triangular faces feature almond-shaped eyes with pupils painted near the top of the eyelids.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 123

Juan Arce

circa 1854–1932, Arecibo

Our Lady of the Pillar circa 1890

Wood, paintOur Lady of the Pillar is the patroness of all Hispanic peoples in the Western Hemisphere because it was on her feast day, October 12, that Christopher Columbus first arrived in the Americas (in 1492). According to lore, she is the first holy apparition in the history of Christianity and the only one that occurred when the Virgin Mary was alive. She appeared to James the Greater (the brother of Saint John the Evangelist) who traveled to Spain (then known as Roman Hispania) to bring the Holy Word to Hispania’s pagans. James was discouraged by the few who converted, but Our Lady of the Pillar appeared to him, standing on a pillar, and surrounded by thousands of angels. She urged him onward and asked that a church be built on the site. The basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar still stands today in Zaragoza, Spain as the first church dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B258

Juan Arce

circa 1854–1932, Arecibo

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1890

Wood, paintJuan produced far fewer carvings than his brothers Ignacio and Pedro. Yet he displays the same skill level and shares figural elements with them such as clothing with wavy lines imitating the fabric’s natural drape. Despite extensive surface carving, this piece retains the rectangular shape of the raw block of wood from which it was carved.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 137

Pedro Arce Sotomayor

circa 1857–1951, Arecibo

Our Lady of Mount Carmel circa 1920

Wood, paintOur Lady of Mount Carmel was a favorite Marian devotion of Pedro Arce. This example is remarkable for the opulent clothing with its implied golden embroidery and the Virgin’s toe emerging from underneath her robe, a rare element for Pedro’s saints. Pedro carves large eyes and arching eyebrows to draw attention to her face. The exceptionally smooth surface is a hallmark of Pedro’s work; he double-sands his santos de palo which here causes the paint coloring the Virgin’s face to glow as if radiating divine light.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 311

Pedro Arce Sotomayor

circa 1857–1951, Arecibo

Our Lady of Solitude circa 1910

Wood, paint, metalPedro Arce was very devout and subject to mystical experiences. Known as “Pedrito El Santero,” he devoted his life to carving santos de palo as a divine mandate. Over his long lifetime, he produced many sculptures in an idiosyncratic style. He often changes the head to body proportions (from 1:7 to 1:3) to focus the viewer’s eye on the carving’s message. Here Pedro draws the viewer’s attention to the Virgin’s sorrow by crowning her with a large, star-studded halo and repeating the motif around the base below her feet and her large hands held in angst against her heart.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 119

Pedro Arce Sotomayor

circa 1857–1951, Arecibo

The Three Kings circa 1920

Wood, paintThe well-carved, large hands and heads of the Three Kings draw the viewer’s eye to their elaborate clothing and restless horses that lend a potent sense of motion to this carving. The piece is fully carved in the round to encourage the devotee to fully connect with the carving to receive the Kings’ divine message.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B43

Ignacio Arce (“El Cachetón”)

circa 1858–1928, Lares

Nativity circa 1900

Wood, paintAlong with figurative stylization, the well-formed base is an Arce family trait. Ignacio Arce places a black rooster among the other attending animals, which may represent Saint Peter’s denial of Christ. The rooster may also refer to its being comparable to Christ because both watch over their flocks (people or hens), and to the cock being a Puerto Rican symbol of hope, confidence, and strength.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 301

Ignacio Arce (“El Cachetón”)

circa 1858–1928, Lares

Our Lady of Sorrows circa 1890

Wood, paint, metalThe most obvious feature distinguishing Ignacio Arce’s works is his figures’ chubby cheeks, earning him the nickname El Cachetón, “the chubby-cheek one.” A second characteristic is the bottle shape of figures, a result of using thicker wood blocks than other santeros. Combined with the pointed crown and contrasting white-painted dress, this carving evinces a strong zigzag rhythm that animates an otherwise static figure, and her arms and large hands invite the devotee to connect with the divine. Our Lady of Sorrows represents the Seven Sorrows of Mary that encapsulate the distresses of earthly life. Mary’s troubles are foretold in the Prophecy of Simeon (in Luke 2:34–35) who predicts the crucifixion and resurrection of her son Jesus as the savior of Israel.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 133

Ignacio Arce (“El Cachetón”)

circa 1858–1928, Lares

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1900

Wood, paint, metalIgnacio creates a standard representation of Our Lady of Montserrat while also taking creative liberties with the mode of presentation. Her multi-faceted crown is not set upon the top of her head but instead is attached at the back in the Andalusian Spanish style of fancy hair or mantilla combs (peinetas).

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 128

Ignacio Arce (“El Cachetón”)

circa 1858–1928, Lares

Saint Anthony circa 1900

Wood, paintThe face of Saint Anthony is a classic example of El Cachetón’s style of chubby cheeked santos de palo. Arce accentuates their shape by building up the base gesso and painting it a striking pink color. The elongated head and stout neck merge gracefully to harmonize with the figure’s bottle form. Typical of Ignacio’s works is the small, adult-looking Jesus who gazes directly at the viewer. Saint Anthony, the patron saint of lost and stolen articles, is one of the most popular Catholic saints. He was an inspirational Franciscan preacher of the 13th century (1195–1231) and demonstrated his faith in the message of Jesus by living a humble life of poverty and service.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 131

Eduvigis Cabán

circa 1818–1891, Camuy

Our Lady of Montserrat Mid-19th century

Wood, paint, metalThe simplistic form of this carving and the Virgin’s somewhat large hands typify the works of Eduvigis Cabán. He also was the first to sculpt the hair as a rounded form on the head as seen here on both the Virgin and Christ Child.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 115

Eduvigis Cabán

circa 1818–1891, Camuy

Virgin (To Be Dressed) Mid-19th century

Wood, paint, glassThe geometric simplicity of the torso and the gentle face with an up-turned nose are hallmarks of the less formal carving style of Eduvigis. The holes in each shoulder accommodated moveable arms, now lost. It was important in Baroque Catholic figures that they could be posed in the manner appropriate for the ceremony during which the saint was the focal point of worship. Note the naturalistic pink blush of the cheeks which makes this Virgin more approachable than the ethereal faces of traditional Baroque sacred sculptures.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B81

Eduvigis Cabán

circa 1818–1891, Camuy

The Three Kings Mid-19th century

Wood, paintMany Cabán family carvers depicted the Three Kings. Here, Eduvigis underscored the magnitude of the Three Kings by carving small, monochrome horses of simplified form in contrast to the larger and more complex figures of the Three Kings.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 44

The All-Powerful Hand circa 1900

Wood, paintThis version of the All-Powerful Hand exemplifies the simplicity of form and iconographic innovation that characterize the Cabán family of carvers. The specific Cabán santero who made this piece has not been determined, but there is no doubt that he was a Cabán and likely of the third or fourth generation.

The All-Powerful Hand is an ancient symbol of divine protection common to Christians, Jews, and Muslims. The Catholic version features small figures of the Christ Child placed on the thumb and Mary and Joseph, Mary’s mother Saint Anna and her father Saint Joachim on the fingers. In this example, the Cabán carver substitutes the Anima Sola ("Lonely Soul") for Saint Joachim. The meaning of this unexpected substitution is unknown although iconographic variations typify the Cabán style.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B59

Florencio Cabán

1876–1951, Camuy

The Three Kings circa 1940

Wood, paintFlorencio Cabán has the widest range of subject matter of all Cabán carvers, although he was particularly fond of the Three Kings. They were the focus of his devotions because of the miraculous outcome of his prayers to the Kings. Florencio found himself in dire straits when he and his wife Ursula fled the home of her abusive father. With no money or luck finding a new home, he vowed to commit himself and his descendants to sponsor a wake in honor of the Three Kings on every eve of Epiphany if the Kings respond to his prayers. Shortly, a relative offered him a small house for his growing family. Florencio gratefully acknowledged the Three Kings’ miracle and sponsored an Epiphany wake each year, which his descendants in Camuy continue honoring. These days, so many people attend the celebration that it is held in the town’s main plaza.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 86

Florencio Cabán

1876–1951, Camuy

Saint Ursula and The Eleven Thousand Virgins circa 1930

Wood, paint, paperToste-Mediavilla collection, B20

Florencio Cabán

1876–1951, Camuy

Saint John the Evangelist circa 1940

Wood, paintSaint John is one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and author of the Bible’s fourth gospel—the Gospel of John. He is usually pictured holding his Gospel as he recites the words of Jesus. Often present in paintings and sculptures of Saint John is the opening line of his Gospel “In principio erat verbum” (“In the beginning was the Word”). Saint John’s other main attribute is the eagle, seen here standing atop a fancy pole or staff. The eagle logo for Saint John comes from a 5th-century poem by Christian writer Sedulius who wrote “More volans aquile verbo petit astra Joannes” (“By means of the flying eagle John reaches the heavens through the Word”).

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 52

Florencio Cabán

1876–1951, Camuy

The Miracle of Hormigueros circa 1940

Wood, paintFlorencio’s personal style permeates this image of the Miracle of Hormigueros. His figures are realistically proportioned, the oval faces have delicate features, and he outlines the eyes with rows of tiny, black-painted dots. The Virgin’s cape is adorned with motifs unlike the orthodox golden stars. They comprise four intersecting short lines with a central dot which is Florencio’s method for depicting flowers—his star motifs have only three short lines. This type of iconographic anomaly is a primary feature of the Cabán family of santeros.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 81

Quiterio Cabán

1848–1941, Camuy

The Three Kings circa 1890

Wood, paintQuiterio extends his father Eduvigis’ simplistic style even further—the horses become thin, elongated, pedestal-like forms elevating the Kings. Their figures are rounded approximations of the human body, and their hands and gifts are only austere visual notions thereof.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 84

Quiterio Cabán

1848–1941, Camuy

Nativity circa 1890

Wood, paintIn contrast to lifelike Nativity scenes, Quiterio’s example epitomizes the Cabán minimalistic style, reducing the figures to the essential father-mother-child group and a couple of farm animals. Quiterio emphasizes the Holy Infant by framing him with the curved bodies of Mary and Joseph bowing over the cradle.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 71

Quiterio Cabán

1848–1941, Camuy

Saint Michael Archangel circa 1890

Wood, paintQuiterio carved this archangel in sections to allow for the active pose of Saint Michael as he readies to slay the dragon-devil. The sculpture’s miniscule base accentuates the devilish figure and magnifies Saint Michael and the divine power that guided his triumph. Note his sculpted hair with its straight line across the back of the head—a prime trait that distinguishes Quiterio’s carvings from those of his sons (Florencio, Ramón, and Manuel).

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 67

Manuel Cabán

1884–1962, Camuy and New York City

The Three Kings circa 1930

Wood, paintManuel’s carvings follow the Cabán relaxed representational style and simplicity of form. His figures tend to be ill-proportioned in comparison to those of his older brother Florencio, yet they retain the direct openness of the Cabán style.

The Cabán carving tradition ended in 1962 with the passing of Manuel. It is fitting that his last santo de palo featured the Three Kings, one of the preferred subjects among four generations of Cabán santeros.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 93

Ramón Cabán

1886–1958, Camuy

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1950

Wood, paint, metalRamón’s carvings are less realistically proportioned than those of his brother Florencio. Yet the Cabán style is clearly present in the oval heads and pleasant faces with well-defined eyes and eyebrows. The Cabán-style decorated collar tops the Virgin’s robe while her halo—a metal half-sphere atop her head—recalls the fancy hair combs worn by stylish women in 19th-century Spain. The especially ornate base, with its carved and painted geometric and floral motifs, is a modernist flourish exemplifying the Cabán family’s inventiveness.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B1

Jesús Antonio Crespo

circa 1847–circa 1920, Aguada and Rincón

Saint Vincent Ferrer circa 1870

Wood, paintDuring his early years of making santos, Crespo prominently carved the pleats and folds of figures’ garments. He decorated clothing with delicate painted designs of short lines, dots, and crosses. His figures are meant to be viewed in the round because Crespo carved and painted each side. The thick, parallel-line eyebrows are a distinguishing element of his works.

Saint Vincent Ferrer (circa 1350–1419) was named after Vincent Martyr, the patron saint of Valencia, Spain where Ferrer was born. He became a Dominican friar at age 19 and was a powerful preacher and tireless missionary. He is patron of reconciliation, builders, and businessmen. Fishermen invoke his aid during storms. Saint Vincent can be recognized by his traditional Dominican white tunic and short red cape. He carries his two most common emblems referring to his preaching—an open book and a trumpet.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 97

José "Pepe" Ramos

circa 1820–1906, Aguada

Saint Peter the Apostle circa 1870

Wood, paintThe carvings by Pepe Ramos are easily distinguished by triangular faces with extremely pointed chins, although the foremost feature is a long, protruding nose. Ramos prefers bright colors, often exploiting the intensity of opposite colors as seen here in the orange lines on the blue-gray background of the base.

Pepe Ramos depicts Saint Peter holding a large key and a cross while a rooster perches behind him. The key represents his authority as the leader of the Twelve Disciples and head of the early Church. It comes from the symbolic statements of Jesus, including “I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 16:19), thereby designating St. Peter as the keeper of the gates of Paradise. The rooster refers to the story that St. Peter denied Jesus three times “...before the cock crows...” (Matthew 26:74), conveying that even saints can falter yet still receive God’s forgiveness.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 151

Pedro Rosa (Pedro José Cuperes Vásquez)

circa 1870–1957, Aguada/San Sebastián/Lares

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1910

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, 120

Jesús Antonio Crespo

circa 1847–circa 1920, Aguada and Rincón

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1870

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, B22

José "Pepe" Ramos

circa 1820–1906, Aguada

Our Lady of Montserrat circa 1860

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, 162

The unique carving styles of Pedro Rosa, Jesús Antonio Crespo, and José “Pepe” Ramos reflect the late 19th-century’s creative broadening of the santos de palo tradition. For example, compare Jesús’s humble depiction of Our Lady of Montserrat (B22) to Pedro’s modernist sculpture (120) reminiscent of the slender, elongated figures of the Art Deco style.

Pedro Rosa’s elegant forms successfully meld realistic faces with abstract bodies (120). Pepe Ramos was a devotee of Our Lady of Montserrat, and his wife Justina Torres Cordero de Ramos, too, was a santera. Their renderings of Our Lady are accessible and inviting to the devotee. Jesús Crespo’s carving of Our Lady of Montserrat (B22) is a tour de force of geometric form and color juxtaposition that conveys the tranquility and serenity of divine presence.

Jesús Antonio Crespo

circa 1847–circa 1920, Aguada and Rincón

The Three Kings circa 1890

Wood, paintJesús Crespo often retains the basic geometric shapes of whatever figure he carves. Here, the bodies of the Three Kings are trapezoids with large heads relative to body size. He minimally carves details of clothing and instead relies on paint to represent capes, tunics, and pants. Crespo’s kings are uncommonly animated, turning their heads to glance at something that caught their eye.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B66

Pedro Rosa (Pedro José Cuperes Vásquez)

circa 1870–1957, Aguada/San Sebastián/Lares

Niche with Saints circa 1920

Wood, paint, giftwrap paper, glassPedro Rosa encapsulates the life of Jesus Christ in this chapel-like box. It depicts the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child on her lap, here in the form of Our Lady of Montserrat. Included are the Three Kings of the Nativity story, San Antonio de Padua, and Christ crucified. Such a complex composition affords the devotee multiple options for devotion and prayers of petition.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 212

José "Pepe" Ramos

circa 1820–1906, Aguada

Saint Francis circa 1870

Wood, paint, metalPepe Ramos depicts Saint Francis in the simple robe with rope belt of a member of the Franciscan Order, founded by St. Francis in the 13th century. The saint carries a large cross symbolizing his founding of the religious Order of Saint Francis. His staff signifies his travels to preach the word of God while living a life of poverty, chastity, and obedience as did Jesus. Pepe Ramos adds the stigmata the saint received in a vision from God on the day of the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. Among the hallmarks of Ramos’ santos are the emotive face of Saint Francis as he looks to heaven and his body reduced to basic shapes. Note the unusually large hands and tiny feet poking from beneath the saint’s robe. Ramos highlights the otherwise simple figure using color and shadow to create an elegant sculpture set atop a well-finished, two-tiered base.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B42

Jesús Antonio Crespo

circa 1847–circa 1920, Aguada and Rincón

The Holy Trinity circa 1890

Wood, paintThis sculpture was made late in Crespo’s life when he had shed his earlier realistic forms for a more austere and abstract style that lays bare the subject matter. Here the three components of the Holy Trinity are uncomplicated portrayals of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. By way of its simplicity, the piece conveys the unity of God composed of God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit. Crespo carves God slightly larger than his son Jesus and accentuates the power of the Holy Spirit by its elevated central position and large tail.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 78

José "Pepe" Ramos

circa 1820–1906, Aguada

The Three Kings circa 1870

Wood, paintPepe Ramos faithfully simulates realistic body proportions, and he carefully carves the Kings’ clothing. He then precisely paints the sculpture within the contours of the carved figures and their garments.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 164

Pedro Rosa (Pedro José Cuperes Vásquez)

circa 1870–1957, Aguada/San Sebastián/Lares

The Three Marys circa 1920

Wood, paintThe relaxed figures gentle folds of their clothing are typical of Rosa’s carvings. He also creates oval faces with arched eyebrows above simple black-pupil eyes, small noses, and dainty mouths. The Three Marys include Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Cleophas, and Jesus’ dedicated disciple Mary Magdalene. Here each Mary holds the palm frond of martyrs.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 108

Carlos Vázquez Sánchez

1904–2003, Ciales

Our Lady of Eternal Help 1997

Wood, paintCarlos Vázquez’s later works are infused with movement and painted details not seen in earlier pieces. This santo de palo was made when he was 93 years old. Despite diminished sculpting abilities, he created an eye-catching figure with a few well-carved intricacies such as the Virgin’s fingers. Yet Vázquez relies more on unrestrained painting to illustrate her face, the wings’ feathers, and the garments’ folds and decorative elements.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 203

Zoilo Cajigas y Sotomayor (Julio Cajigas Matías)

1875–1962, Aguada

The Sacred Heart of Mary circa 1930

Wood, paint, metalToste-Mediavilla collection, B26

Eleno Cajigas Badillo

1915–2003, Aguada

Our Lady of Mercy 1997

Wood, paint, metalToste-Mediavilla collection, B35

A comparison of these two carvings by father and son frames the aesthetic and technical changes of the late 20th century. Zoilo’s Sacred Heart of Mary follows the traditional materials, carving customs, and representational formats. Zoilo’s figure expresses his deep spiritual belief in an unfettered manner whereas Eleno’s style, including modernistic forms and pigments, achieves the same end by featuring Our Lady of Mercy’s principal symbols of divinity. The star-and-moon-marked ramp hides a small box for petitions to the Virgin.

Carlos Santiago

born 1947, Ponce (resides in Massachusetts)

The Virgin of Bethlehem 2011

Wood, paintCarlos Santiago carves a fine image of the Virgin of Bethlehem who is also known as the Virgin of Milk. Illustrations of Virgin Mary breastfeeding the Christ Child were common during the 16th century but dropped out of fashion during later centuries. Santiago revives this convention while changing the orthodox colors of the Virgin’s attire.

José A. Román Ramos

born 1973, Quebradillas

Portrait of José Campeche y Jordán 2009

Wood, paintJosé Román honors the renowned Puerto Rico-born painter José Campeche y Jordán (1751–1809). His father, a formerly enslaved person who bought his freedom by carving altarpieces, taught don José how to paint. He also studied with the Spanish artist Luis Paret. Campeche is considered among the best Rococo artists in the Americas, and he often used bright colors like those he saw in the Puerto Rican landscape.

By choosing the santos de palo format for Campeche’s portrait, José Román likens the artist to a Puerto Rican saint. He also references the santos de palo tradition by showing Campeche’s canvas as half painting and half wood carving.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B131

José Luis Peña Burgos

born 1965, Orocovis

The All-Powerful Hand 2002

Wood, paintSanteros of the late 20th century explored a wide variety of religious subjects and devised variations of traditional imagery. Yet in the time-honored santeros manner, Peña Burgos has a personal connection to each piece, sharing his spiritual energy with the wood as he carves. His All-Powerful Hand pictures the customary genealogy of Jesus but moves the Christ Child from the thumb to the pinky finger. The All-Powerful Hand emerges from a large cloud while the saintly figures stand on smaller blue ones.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 70

Juan Rivera Jiménez

born 1969, Quebradillas

The Christ Child of Atocha 1998

Wood, paint, straw, clay, plasticJuan Rivera’s Christ Child of Atocha does not wear the typical pilgrim’s brown cloak over a plain blue robe. Instead, his Christ Child sports an Asian-style robe patterned with the “Evil Eye,” an ages-old emblem believed to protect the wearer from harm. Rivera includes the traditional iconography of a basket of bread and fish, but he adds others filled with fruits and vegetables. Juan Rivera weaves baskets, too, although he makes his living as a schoolteacher.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 241

José Luis Millán Figueroa

born 1959, San Germán

Our Lady of Valvanera 2002

Wood, paintJosé Luis Millán’s sculpture simulates the eighteenth-century painting of Our Lady of Valvanera by Mexican artist Miguel Cabrera (Philadelphia Museum of Art), though Millán takes liberties, substituting a griffin-like creature for Cabrera’s eagle and depicting the Virgin with pearl-white skin rather than Cabrera’s darker-skinned Mexican woman. The Virgin of Valvanera is venerated in the town of Coamo, Puerto Rico, whose townspeople begged for her intercession to alleviate the epidemic of cholera that struck the town in 1683.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 295

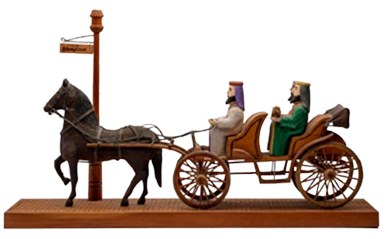

Wilzen Pérez

born 1944, Guánica

The Three Kings in a Carriage 2003

Wood, paintWilzen Pérez follows the mid-20th-century trend of incorporating lived experiences and local imagery in his carvings. This example places the Three Kings riding in a 19th-century carriage like those that ferry tourists around Old San Juan. The carriage travels down Calle Bonafoux, a short street in the Hato Rey district of San Juan where the Toste-Mediavilla family lived.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 75

Salamanca

20th century, Aguadilla

The Three Kings circa 1940

Wood, paint, glitterThe widest variety of artistic experimentation is seen in the Three Kings. Salamanca was among the early experimenters. Although he follows the standard format of the Kings on horseback, his monarchs are unusually playful—almost clown-like—in their spotted clothing and steeds, outsized hands, and dusting of glitter on their clothes.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 114

Isaac Laboy Moctezuma

born 1954, Quebradillas

The Three Little Kings on Toy Horses 1996

Wood, paintIsaac Laboy's inventiveness is in full flower with his transformation of the Three Kings into children riding hobby horses. Rather than gold, frankincense, and myrrh, the child-Kings bring symbols of Puerto Rico – a native coqui tree frog, a dove, and a flor de maga blossom (the Puerto Rican hibiscus), the greatest gifts of all from Isaac’s viewpoint.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B121

Vladimir Vélez

born 1964, Trujillo Alto

The Virgin of The Three Kings 1996

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, B49

Roberto Rivera Rivera

1945–2005, Corozal

The Virgin of The Three Kings 1997

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, B290

Isaac Laboy Moctezuma

born 1954, Quebradillas

The Three Kings and the Three Marys 1998

Wood, paint, leatherToste-Mediavilla collection, 12

José Luis Millán Figueroa

born 1959, San Germán

The Three Kings and the Three Marys 1999

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, 276

Isaac Laboy Moctezuma

born 1954, Quebradillas

The Three Kings 1998

Wood, coatingIsaac Laboy is equally adept at creating carved santos de palo and foregoing any further decorative additions. The lack of paint allowed the artist to give each King a different expression and subtle facial differences. The gifts they bring are typically Puerto Rican—a bowl of local fruits, a basket of fish or bread, and a bucket of water.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B260

Isaac Laboy Moctezuma

born 1954, Quebradillas

Our Lady of Montserrat 1999

Wood, paintIsaac Laboy positions her in the center of a flor de maga blossom (maga tree flower), the national symbol of Puerto Rico since 2019. This lush flowering tree is found throughout the island and is a popular ornamental landscape planting.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B118

Orlando Vélez Rivera

born 1959, San Germán

Our Lady of Montserrat 2001

Wood, paintOrlando Vélez pictures the Montserrat mountain behind the Virgin as if it were a jungle-covered mountain of Puerto Rico’s central highlands.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 344

Norberto Cedeño Calderón

1894–1985, Toa Alta

The Miracle of Hormigueros 1966

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, 326

Israel Gerena Olán

born 1958, New York, Quebradillas

The Miracle of Hormigueros 1997

Wood, paint, strawToste-Mediavilla collection, 298

Amaury Lugo

born 1946, Quebradillas (resides in Japan)

The Miracle of Hormigueros 1997

Wood, paintAmaury Lugo’s background pictures Puerto Rico’s rounded karst mountains rather than the serrated peaks surrounding the Spanish shrine.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 325

Domingo Orta Pérez

1929–2007, Ponce

The Miracle of Hormigueros 199

Wood, paint, strawDomingo Orta substitutes a flor de maga blossom (Puerto Rican hibiscus) for the orthodox Catholic golden orb typically held by the Virgin.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B55

THE LONELY SOUL

The Lonely Soul represents a person, usually a woman, suffering in Purgatory and expressing heart-felt penitence that will release her to Heaven. Compare the 19th-century subdued penitent figure by Florencio Cabán (69) to the deep spiritual remorse expressed in the carvings by Nitza Mediavilla and María Sánchez (B28, B11).

Florencio Cabán Hernández

1876–1951, Camuy

The Lonely Soul circa 1940

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, 69

Nitza Mediavilla Piñero

born 1949, San Juan

The Lonely Soul 1994

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, B28

María Sánchez

born 1954, Corozal

The Lonely Soul 1996

Wood, paintToste-Mediavilla collection, B117

Olga Rivera

born 1949, San Sebastián

Saint Michael Archangel 1998

Wood, paintSaint Michael Archangel is the chief of all God’s angels and the guardian of both Biblical Israel and the later Catholic Church. Mohammed states that both Angels Michael and Gabriel showed him Paradise and Hell. In the Christian faith, Saint Michael’s attributes serve as the Christian contrast to heretics (Epistle of Jude 1:8). This key role is symbolized by his battling Satan (Revelation 12:7–12).

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B304

Carmen Beníquez

1946–2016, Aguada

Our Lady of Mercy 1998

Wood, paint, metal

Our Lady of Mercy is the protector of Christians. She is usually shown spreading her mantle in

protection of

small human figures who flank her legs or stand below her. Depending on who commissioned an image, the

small

figures may symbolize all of humanity or a guild, family, or religious order. Our Lady of Mercy is the

patron

saint of Barcelona, the origin of many emigrants to Puerto Rico in the 19th century.

Our Lady of Mercy usually is pictured in a long robe and mantle of contrasting colors. Carmen Beníquez chooses the less common white robe and mantle embellished with gold-thread embroidery. The Virgin holds a silver chain in her right hand and a cord connecting her to two tiny human heads signifying humanity or perhaps the family that commissioned this santo de palo.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 265

SAINT URSULA AND THE ELEVEN THOUSAND VIRGINS

There is little confirmed information about Saint Ursula and her nameless group of holy virgins beyond their being martyred by invading Huns in the 4th Century. Saint Ursula’s popularity in Puerto Rico originates in an unsuccessful British attack on San Juan in 1797. A prayerful procession of ladies with torches fooled the English into thinking the Spanish had received reinforcements, and the invaders withdrew.

Luis Felipe ("Wiso") Franquí Lasalle

born 1972, Quebradillas

Saint Francis 2014

Guayacan (Lignum vitae)Luis Felipe Franquí oriented the wood block of guayacan (Lignum vitae) so that its light-colored vein accentuates the saint’s arms and signature icons—the Cross and the skull. The grain’s vertical orientation allowed Franquí to imply the natural drape of the saint’s long robe by the gently curving, lighter brown grain on the garment’s front.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 22

José A. Román Ramos

born 1973, Quebradillas

Our Lady of Mount Carmel 2002

Various tropical woodsJosé Román’s selective use of different woods demonstrates his deep understanding of the inherent qualities of Puerto Rico’s tropical woods. In this carving he intersperses separately carved sections from distinctive tropical woods.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B170

Isaac Laboy Moctezuma

born 1954, Quebradillas

Our Lady of Divine Providence 2009

Quina wood, coatingAn especially captivating piece is Isaac Laboy’s impressionist portrayal of Our Lady of Divine Providence. Laboy believes the divine spirit of the saint is in the wood, and the santero simply reveals it. Here Laboy has gently drawn out Our Lady of Divine Providence from the contours of a gnarled tree root. Laboy let the root determine the general shape of the piece while carefully manipulating select areas to masterfully meld the natural and the carved surfaces.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 341

Luis Felipe ("Wiso") Franquí Lasalle

born 1977, Quebradillas

Saint Michael Archangel 1998

Spanish cedarTwo different shades of light brown Spanish cedar enliven this dramatic rendering of Saint Michael Archangel. The light-colored wood of Saint Michael contributes to the soaring form while the similarly hued fire engulfs the defeated Satan as he falls into Hell.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 228

José Antonio Orta

born 1954, Ponce

The Vigil and Promise of the Three Kings 1998

Wood, paint, strawOrta captures the primary elements of the Vigil of the Three Kings. A table-turned altar displays a santo de palo carving of the Three Kings while a local band performs décimas, an improvised poetic form like today's hip-hop and rap compositions. The Spanish brought the décima poetic form to Puerto Rico, and it became the backbone for música jíbara, rural Puerto Rican folk music played on the cuatro, maracas, and güiro. José Orta honors this heritage by dressing his musicians in jíbaro-style straw hats.

The Spanish brought the décima poetic form to Puerto Rico, and it became the backbone for música jíbara, rural Puerto Rican folk music played on the cuatro, maracas, and güiro. José Orta honors this heritage by dressing his musicians in jíbaro-style straw hats.

A décima poem comprises a ten-line stanza that follows the strict rhyming pattern: ABBAACCDDC. Each line must have no more than eight or nine syllables depending on whether the last word in the line is emphasized on its last or penultimate syllable. A décima poem is typically an improvised musical performance, composed on the spot by the performer, and forms a central element of the vigil. Longer formal décimas are memorized and performed especially during Epiphany, their topics being appropriate to the Christmas season.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B317

Luis Millán Rivera

born 1954, Ponce

The Vigil and Promise of the Three Kings 2012

Wood, paintA woman kneels in reverence as she prays to the Three Kings. A celebrant holds above his head a santo de palo carving of a chapel housing the Three Kings. Traditional music is provided by men playing the 4-string cuatro and a 6-string guitar while another plays a güiro, a hollow gourd rasp for making rhythmic scraping sounds. The small, 4-stringed cuatro was joined by a 10-string version at the end of the 19th century, both of which retain the cuatro name. The instrument has extended its influence outside of Puerto Rico and today is played by a variety of musicians from folk to rock music.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B48

Victor Rivera Mercado

born 1958, Barceloneta

The Vigil and Promise of the Three Kings 2019

Wood, paintVictor Rivera transforms the Three Kings into three men wearing the traditional attire of the jíbaro, the mixed-race peasants of Puerto Rico’s hinterlands. It comprises a loose-fitting white shirt with a wide collar, red neckerchief tie, and white pants. Rivera cleverly alludes to the island’s three dominant races by changing the Kings’ hair traits, skin colors, and types of pants. The Spanish King has pink-cream skin, wavy dark hair, a modern-style beard, and wears khaki pants. The African King has dark skin, curly black hair, and wears jíbaro-style white clothing. The native Taíno King has cream-colored skin, straight black hair, no beard, and wears blue jeans. They all wear conventional golden crowns. Rivera’s instruments are especially detailed with actual strings on the cuatro, a metal scraper for the güiro, and maracas swathed in the design of the Puerto Rican flag.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 294

Félix “Pipo” Rivera

born 1961, Orocovis

The Vigil and Promise of the Three Kings 1994

Wood, paint, metal, stringToday, santeros frequently render the Three Kings holding the standard instruments of a jíbaro band (cuatro, maracas, and güiro). This radical innovation was not well-received when first introduced in the 1950s by Domingo Orta Pérez (1929–2007), the father of José Antonio Orta, the carver of The Vigil and Promise of the Three Kings (B317) in this case. The Three Kings as jíbaro musicians has become a beloved composition expressing both religious faith and Puerto Rican culture.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 197

Victor Rivera Mercado

born 1958, Barceloneta

The Promise of the Three Kings 2019

Wood, paint, cord, seedsVictor Rivera’s carving summarizes the Epiphany celebrations in Puerto Rico. The night vigil is signified by the candle and rosary on the table, and the figure, depicting King Melchior dressed in jíbaro-style attire but wearing a golden crown, brings a votive carving of the Three Kings for the family altar (the table). The night’s décimas and music are implied by Melchior’s maraca, painted with the Puerto Rican flag, and the cuatro on the table. A tiny tricycle underneath the table represents the Kings’ gifts for the children which they receive on Three Kings Day.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B2

José René Rivera

born 1967, Corozal

The Three Kings Inside a Pastel de Plátano 2017

Wood, paintThis clever carving portrays a pastel, the essential food for Puerto Rican celebrations. Pasteles are similar to a Mexican tamale but made from plantain or yucca dough instead of maize. They are filled with savory meat, then wrapped in banana leaves, and steamed. Here José Rivera carved a wrapped pastel which opens to reveal its treasured contents — not the food but the Three Kings following the Star of Bethlehem to the Christ child.

Pasteles are central to the Epiphany events, especially the parrandas. Family members and friends walk to neighbors’ homes where they perform décimas and aguinaldos–ten- and six-line poetic songs with religious and secular themes performed with musical accompaniment on traditional instruments. Neighbors open their homes to the performers, and everyone joins in the music, eats pasteles and rice pudding, and drinks coquito (an alcoholic beverage like eggnog).

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 314

José A. Rosado Figueroa

born 1941, Toa Alta

The Virgin of the Three Kings 1996

Wood, paintAs a subtle nod to cultural identity, José Rosado places Puerto Rico’s flag in the crown of the Virgin of the Three Kings. Rosado is among the select group of accomplished santeros who are teaching the santos de palo tradition to the next generation of aspiring carvers.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 231

Luis Raúl Nieves Román (“Pichilo”)

born 1950, Dorado

Nativity 1997

Wood, paint, metalThis Nativity scene by Luis Raúl Nieves evokes a rural setting in Puerto Rico. He replaces the stable with a tormentera, an A-shaped rural shelter that protects people and livestock from the violent winds of hurricanes, here with its requisite tied-down roof. Nieves perches a rooster atop the doorway, a common Puerto Rican symbol, and fills the trees with colorful birds like those of the island’s tropical forest. Luis, like José Rosado, is one of today’s distinguished teachers of the santos artform.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 288

Emanuel Nieves Dorta

born 1982, Hatillo

The Three Kings 2003

Wood, paintEmanuel Nieves Dorta’s carving of the Three Kings bringing gifts to the Christ Child is a statement of civic pride for his hometown of Hatillo. Gaspar, the youngest King (on the left), presents the town’s official staff carried during Carnaval parades while he cradles under his right arm Hatillo’s coat of arms. In the center, Melchior extends outward the town’s flag on which sits a heart, symbolizing love of his hometown. Baltasar holds small plaques with the town’s emblem and Hatillo’s distinctive Carnaval mask. For Nieves, the Kings’ gift is Hatillo where he was born and lives today.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B136

Myrna Báez

born 1955

Puerto Rican Nativity 1997

Wood, paint, metalMyrna Báez makes an overt statement of Puerto Rican identity in the large backdrops of her Nativity scene. The center backdrop displays Puerto Rico’s national flag. On the left is a coquí tree frog sitting on a wide leaf and on the right is a flor de maga blossom (Puerto Rican hibiscus), the nation’s national flower. Báez punctuates her spiritual and cultural message by physically connecting the flag backdrop to the Star of Bethlehem hovering above the scene.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B351

Isaac Laboy Moctezuma

born 1954, Quebradillas

The Three Kings in a Paper Bag 2006

Wood, paintThe Three Kings are enclosed in a paper bag and peek out from small tears near its top edges. The shape suggests a paper-bagged six-pack of beer torn by the bottles’ tops while being carried to an Epiphany celebration. Laboy has transformed the beer bottles into the Kings who peer out from inside the paper bag.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, 42

Jesús Nieves Dorta

born 1982, Hatillo

Jíbaro Promise of the Three Kings 2002

Wood, paintA typical jíbaro man wears the customary white shirt and wide-brimmed straw hat of Puerto Rico’s mixed-race countryfolk. He carries a modest carving of the Three Kings inside a box much like the Unidentified Carver’s santo de palo (B369). Such carvings held an honored position in celebrants’ homes during the Vigil of the Three Kings and Epiphany celebrations—the most consequential of all holidays in Puerto Rico summarized by this unpretentious figure.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B146

Unknown Puerto Rican Carver

20th century, Puerto Rico

The Three Kings in a Box Early 20th century

Wood, paintThe casual carving and square figures are those of an itinerant santero who used wooden planks and inexpensive paints to create a compelling depiction of the Three Kings on horseback.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B389

Jaime Rodríguez Heredia

born 1958, Jayuya

The Three Kings 2001

Ortegón woodThis substantial carving successfully merges form and medium into a transcendent rendering of the Three Kings—the most customary of all santos de palo themes in Puerto Rico. Rodríguez used native ortegón wood (Coccoloba rugosa), a hard tropical wood resistant to rot, taken from the foundation of an old house. Although difficult to carve, ortegón wood is unsurpassed in its very fine grain and exceptionally smooth and shiny surface when polished.

The artist barely carved the lower half of the Kings, leaving intact the wood’s weathered surface. He carefully carved the Kings’ upper torsos, hands, and heads with special attention to the textures of their beards and hair. The effect is of ageless Kings materializing from ancient times as influential icons relevant to our contemporary world.

Toste-Mediavilla collection, B61